The Tipping Point

For millennia, mountains held their distance. Not out of disdain, but by nature—by their steepness, their storms, their silence. Veiled in ice and myths, they kept the human world below.

But something started to change. A turning of the mind was slowly taking place. After centuries obscured by divine mystery, the human spirit began to long for something else, for something more. Knowledge. Proof. Clarity. A different kind of light. In Europe, this awakening took a name: “le siècle des Lumières”, the Enlightenment. The darkness of superstition gave way to the dawn of inquiry. What was once sacred now seemed accessible. What had been feared became challengeable. Science replaced myth as a way of reading the world.

New horizons opened across oceans. The known world expanded. With each new continent discovered, a new question took root: what if nothing is truly unreachable? The Age of Exploration was both geographic and metaphysical. In 1492, the same year Columbus crossed the Atlantic, a different kind of expedition took place in France. By royal command, a man named Antoine de Ville climbed Mont Aiguille (2 087 m), a solitary, vertical spire once considered impossible to climb. Using ropes and ladders, it was the first recorded ascent of a mountain for no other reason than to reach the top.

Mountains began to shift from “axis mundi” to scientific playgrounds. The great upheavals of astronomy accelerated this transformation. In 1543, Copernicus proposed that the Earth was not the center of the universe, but one planet among others, orbiting the sun. Galileo discovered the moons of Jupiter with their own revolutions. Newton described gravity and the laws that govern planetary motion. In the wake of this “Copernician revolution”, the idea of “center of the world” was profoundly shaken. The cosmos was changing shape and so was our place within it. From Aristotle’s geocentric order, humans stepped into a dynamic system governed by forces that could be studied, modeled or predicted.

And with this intellectual momentum came breakthroughs in all directions:

- In 1749, Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon began publishing his “Histoire naturelle”, laying the foundations of modern geology and putting forth that the Earth was far older than the biblical account suggested.

- In 1785, James Hutton, father of modern geology, introduced the concept of “deep time” and gradual geological processes in his seminal work, “Theory of the Earth,” marking a radical departure from biblical chronology.

- Mathematicians like Leonhard Euler (1707–1783) and Joseph-Louis Lagrange (1736–1813) revealed hidden harmonies in nature, using differential equations to describe planetary motion and fluid dynamics.

- In chemistry, Antoine Lavoisier (1743–1794) identified and named elements like oxygen and hydrogen, demonstrating that matter obeys strict physical laws.

- Galileo’s telescope (1610) had already revealed Jupiter’s moons, but by 1781, William Herschel discovered Uranus, expanding the known solar system.

- In the opposite direction, Robert Hooke’s early work “Micrographia” (1665) described the microscopic structure of cork, coining the term cell to describe the basic unit of life.

In this changing world, mountains were no longer the abode of gods. They became part of the system: objects to study, altitudes to record, names to assign. In 1786, two men—Jacques Balmat and Michel-Gabriel Paccard—stood for the first time at the summit of Mont Blanc (4 810 m), not as pilgrims, but as explorers. Their effort was sparked by a scientist: Horace-Bénédict de Saussure, who had promised a reward to anyone who could find a way to the top.

Was it a coincidence that alpinism emerged at the same time as modern science? Or was it part of the same transcendent movement: the desire to rise, to know, to push the boundaries of the old world? We no longer feared the mountains or the gods; we were going out to challenge them.

The Age of the First Ascents

The 19th century marked a shift in our relationship with the mountains. No longer seen as stairways to the gods, they became frontiers to explore, measure, and understand. A generation of men began to look up at the vertiginous slopes, not with fear or reverence, but with a quiet resolve to climb them.

Everything was starting to align: scientific theories redefined our place in the cosmos. Technology gave us new tools to make sense of the world. We had barometers to measure atmospheric pressure, topographic surveys, alpenstock “alpinus baculus”, nailed boots, early ice axes. The first alpine clubs were created in UK, Austria, Italy, Switzerland and Germany. Following the Industrial Revolution, a new social class—wealthy, educated and leisured—emerged, with the means to afford expensive hobbies. Climbing mountains became the most unproductive and noble of gestures: a rebellion against utility itself.

Armed with science and stubbornness, they began to rise, making possible things previously unconceivable.

- 1854: The Wetterhorn (3 692 m) was climbed by Alfred Wills, a British judge. His book, Wanderings Among the High Alps, helped spark the romantic imagination of the English elite.

- 1855: Mont Pelvoux (3 946 m), long believed to be the highest point in the Écrins, was climbed by Victor Puiseux. The climb revealed that Barre des Écrins (4 102 m), not Pelvoux, was in fact the tallest peak in the region.

- 1855: The Dufourspitze (4 634 m), highest point of Monte Rosa, was summited by a larger team.

- 1861: The Weisshorn (4 506 m), one of the most elegant and isolated Alpine peaks, was climbed by John Tyndall, physicist and mountaineer, with guides J.J. Bennen and Ulrich Wenger.

- 1865: The Matterhorn (4 478 m) was conquered by Edward Whymper, after multiple failed attempts. The triumph turned tragic: four climbers fell to their deaths on the descent, their rope snapping mid-air. The mountain was won, but at a high cost.

The mountaineering impulse could not be contained in Europe:

- 1874: Fanny Bullock Workman, one of the earliest woman explorers, began her expeditions in the Himalayas.

- 1877: The first alleged ascent of Mount Elbrus (5 642 m) by Killar Khashirov, a Kabardian guide working for the Russian army. Yet, the first recorded ascent of Mount Elbrus was by a British expedition led by F. Crauford Grove.

- 1897: Aconcagua (6 961 m), highest peak outside Asia, was climbed by Matthias Zurbriggen, a Swiss guide in an expedition led by Edward FitzGerald.

- 1902: Kangchenjunga (8 586 m) was attempted by Aleister Crowley and Oscar Eckenstein—although unsuccessful, it is the first serious approach to a Himalayan 8 000er.

- 1924: George Mallory and Andrew Irvine disappear on Everest, the summit still untouched, yet symbolically breached.

[NB. This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive account of all the great first ascents, nor a complete roll call of names and dates. Entire books already do that, and do it well. I’ve simply chosen to highlight what felt most resonant within the frame of this article.]

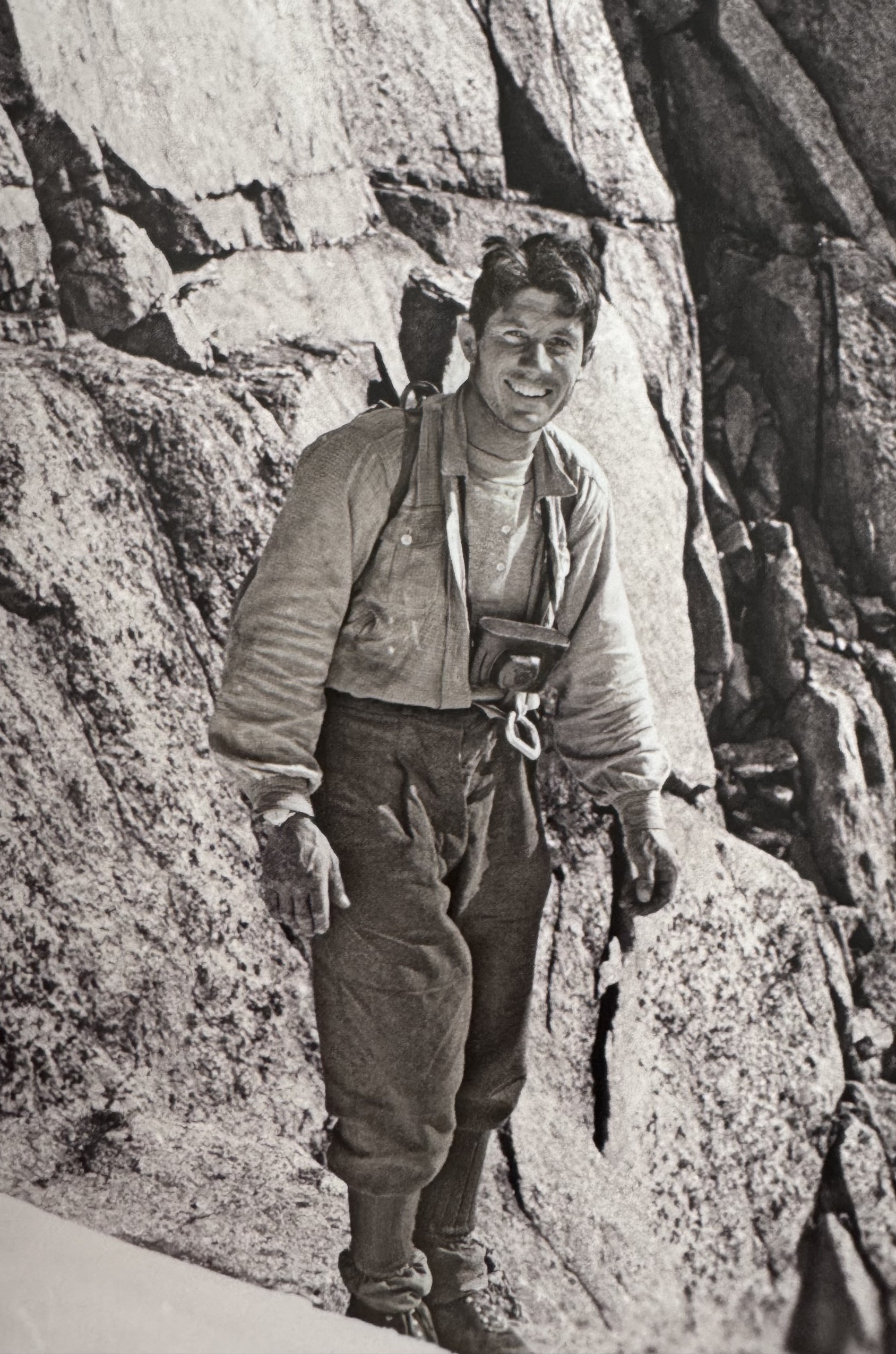

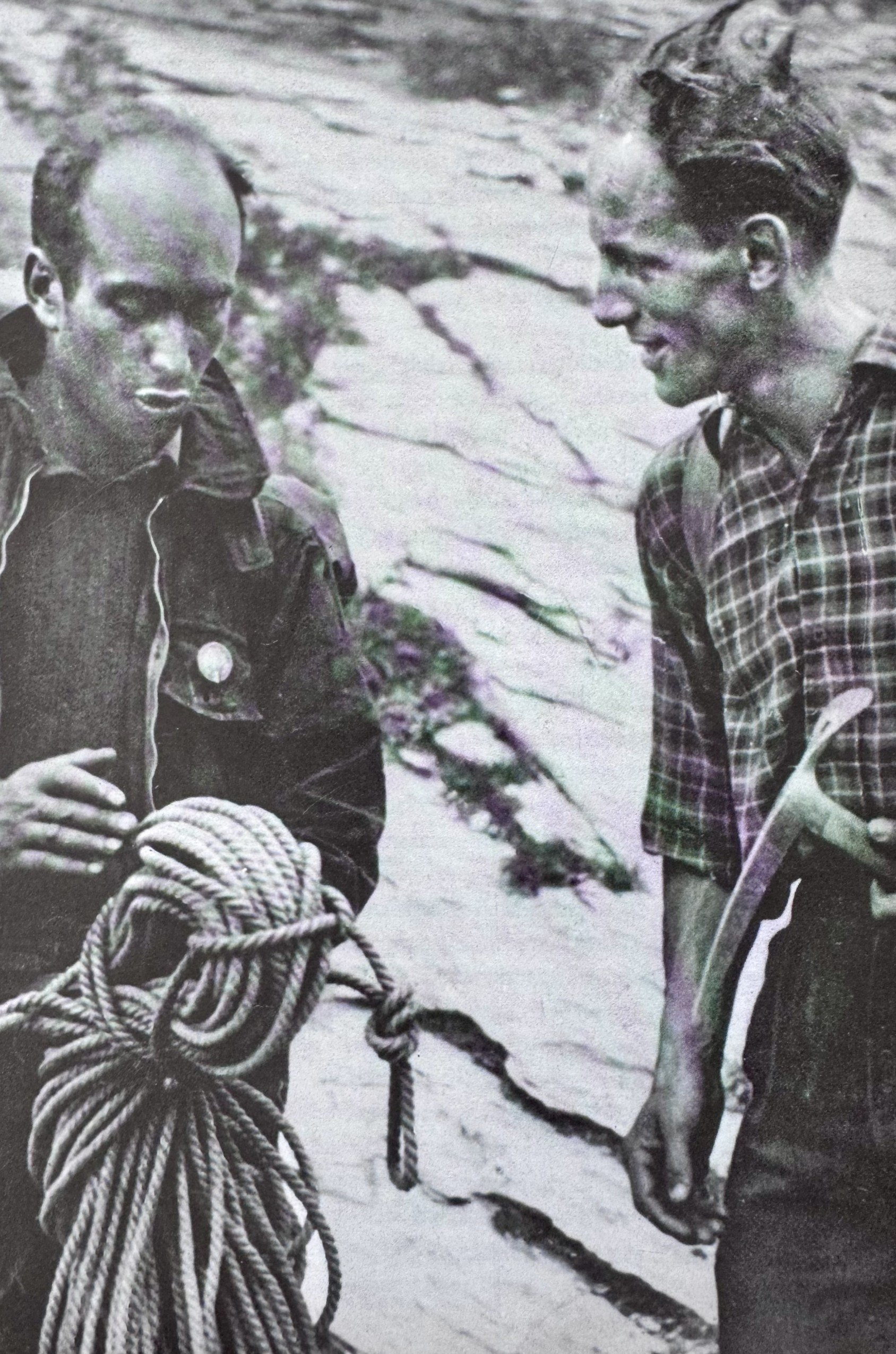

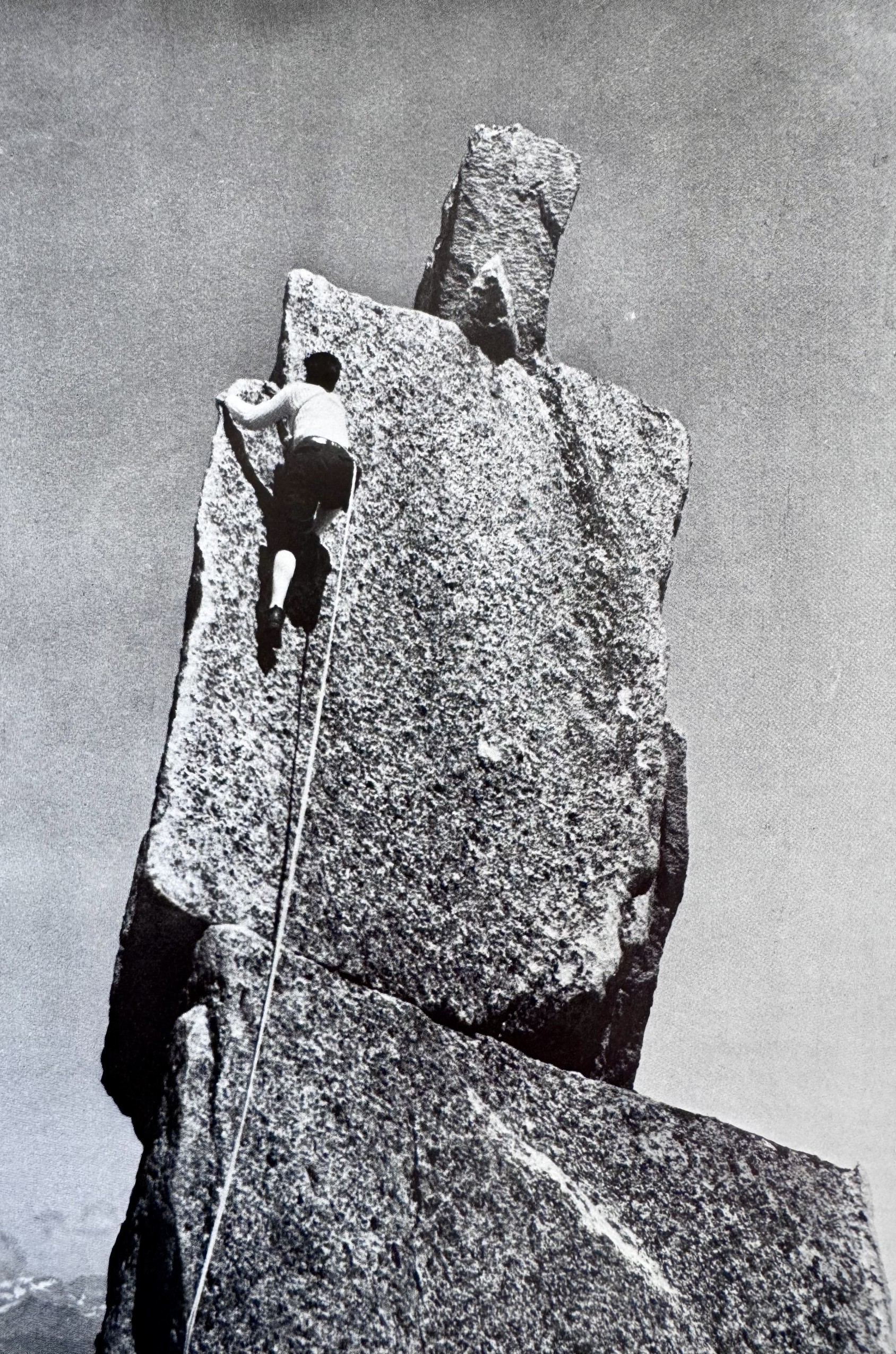

Each summit conquered was a rewriting of the archaic world: where gods once ruled, now men walked. Man climbed with wool jackets, hemp ropes, and leather boots with hobnails. No GPS. No Gore-Tex. No rescue helicopters. They carried little except determination, perseverance, and something close to madness.

Pic du Maupas, Pyrénées.

The Refuge de Tuquerouye, built in 1890, is the oldest refuge in the Pyrenees.

Climbing in the Name Of

In an age increasingly obsessed with productivity, economic gain and measurable output, why would men sacrifice time, resources, even life itself, for something so unproductive, so futile?

Motivations are as varied as the climbers themselves. Curiosity. Glory. Solitude. Proof. Grace. Transcendence. Patriotism. Beauty. Obsession. Some climbed in the name of science. Others, for their country. Some, for no reason at all—except that the mountain was there. Each climber carried their own reasons. But, all of them shared the same gesture: the will to rise.

Some of the early ascents were undertaken in the name of knowledge. Climbing meant collecting data, observing altitudes, measuring pressure, mapping terrains. Horace-Bénédict de Saussure’s mission on Mont Blanc in 1786 was less of an ego quest but a geophysical endeavor. He sought data on air pressure, magnetism, geology. Reaching the summit meant adding a datapoint to the vast and expanding map of the world. To climb the summit was to claim knowledge.

There was also the urge to explore, the human need to see and touch what lies beyond the edge of the map. Climbing turned terra incognita into known territory. It was a way of “taming” chaos, a reenactment of the eternal return. Mountains offered one of the last frontiers of Earth.

Then came the appetite for power. To name is to possess. To flag a summit is to stake a claim. In the 20th century, the mountains became arenas of national pride and a display of power.

The race for the 8000-meter peaks became a version of the Cold War in wool and crampons:

- 1950: Annapurna I, climbed by the French expedition led by Maurice Herzog, the first 8000-meter summit ever reached. One still wonders how they chose Annapurna over Dhaulagiri, believing it to be the safer of the two. Modern statistics reveal the irony: Annapurna remains the deadliest of all eight-thousanders, with a fatality rate of over 30%.

- 1953: Everest, reached by Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay. The roof of the world, finally touched.

- 1954: K2, conquered by the Italian expedition led by Achille Compagnoni and Lino Lacedelli, with a crucial contribution from Walter Bonatti, whose selfless effort and forced bivouac in the death zone became one of the great moral stories of mountaineering.

If we set aside the controversies, each summit stood as a symbolic high ground, proof of national endurance, technical mastery and ideological amplitude.

And yet, beyond politics, beyond science, another kind of climber emerged. For many, the mountain became a place for inner elevation and lyricism.

Lionel Terray, in his autobiographical “Les Conquérants de l’inutile”, called mountaineering “the conquest of the useless.” He wasn’t dismissing it: he was celebrating it. Climbing was a poetic rebellion against pragmatism, a ritual of meaning in a disenchanted world ravaged by war.

“What we loved in climbing was the feeling of defying gravity, of dancing above the void, of running vertically—the sensation it gives when practiced with virtuosity. Then, like the aviator in the sky or the skier on snow, man feels freed from his crawling, earthbound condition and becomes a chamois, a squirrel—almost a bird!” (Lionel Terray, Les Conquérants de l'inutile)

For Gaston Rébuffat, another Alpine icon, mountaineering was about harmony, not conquest. Rébuffat believed that true alpinism required two things: enthusiasm and lucidity. Enthusiasm to leave behind comfort, to embrace fatigue, cold, hunger—not as sacrifice, but as a return to our natural strength. And lucidity: the rare, quiet courage to know one's limits while pushing them a little bit further, to evaluate honestly, to turn back if needed. For him, climbing was not about conquering at all costs, but about walking a fine line between passion and wisdom.

And then there was Walter Bonatti. What a man! The last romantic of all mountaineers. Hero of impossible climbs, Bonatti believed that the true summit was within. His solo ascents, especially on the Grandes Jorasses or the Matterhorn, were less about reaching the top than about facing the self—naked, stripped of pretense, both vulnerable and strong.

“(…) True alpinism is something else: above all, a reason for inner struggle and conquest, for refinement and spiritual joy, with the mountain as both its ideal and magnificent field of action. The fatigue, the suffering, the deprivations that almost always accompany a summit ascent become meaningful conditions, which the alpinist accepts in order to forge their strength and character.

Moreover, in this climate of battle, in direct contact with challenges, with the unknowns and the thousand dangers of the mountain, the alpinist is revealed as they truly are—stripped bare with ruthless sincerity, with their virtues and flaws, in their own eyes and in the eyes of others.” (Walter Bonatti, À mes montagnes)

For them, climbing was never just a sport. It was a mirror, reflecting human fragility, but also human grace. It was a dialogue with gravity. A ritual of courage, taking the human to Herculean proportions. A sacred dance at the edge of the world.

What began as a rebellion against the old order—against gods, limits, fear—slowly turned into something else: a form of return. Not to religion, but to a new kind of spirituality. Not to dogma, but to freedom. To climb was to stand once again at the crossroads, between the mundane and the sacred, between the self and the universe. The mountain no longer belonged to the gods. But it had never ceased to be sacred. To reach the summit is to enter a suspended moment where everything else falls away: ego, noise, gravity itself. In that thin air, only silence remains, and perhaps, a glimpse of immortality.

© Madalina Diaconescu, July 2025