Now that every mountain has been climbed, mapped, measured… where do we go from here?

In ancient times, mountains were sacred and inaccessible. Then came the age of conquest, with ropes, ice axes and the steel will of the first mountaineers. Today, we are living in another chapter—the age of mountains as consumption goods. Mountains have become lifestyle accessories, currencies of identity, business models. From valley to summit, they are booked, branded, hashtagged, overrun, covered in logos and GPS tracks.

This article is an attempt to understand how our relationship with the mountains has evolved, driven by our economic system, technological progress, social media, and our growing appetite to see and be seen. The sacred, the symbolic, the sublime: are they are still up there?

The Mountain as Lifestyle

After Thorstein Veblen, “The Theory of the Leisure Class”, 1899

Veblen introduced the idea of conspicuous consumption: we consume not just to meet our needs, but to signal status. Leisure, he said, reflects social belonging and dynamics; hobbies, like other goods we consume, are signs of class, identity, and wealth. More than a century later, now that we have more money, spare time and knowledge than ever, his theory sounds like a prophecy.

There was a time when going to the mountains meant stripping life to its essence, walking away from the comfort, the certainty and the flaws of civilization. With minimal equipment and maximum humility, mountaineers moved toward the raw and faced the forces of nature.

Today, it’s quite the opposite. Entering the mountains means entering another coded, curated world. In a society where leisure speaks the language of classes, the mountain becomes a pedestal for social distinction. A ski trip to Zermatt or Courchevel signals not only taste, but wealth. A Gore-Tex shell or a sleek Nordic fleece it’s not just gear: it’s social grammar. Paying for an expedition to Mount Kilimanjaro speaks volumes about who you are, what you value, and how you choose to be seen.

To climb, to trail run, to ski-tour, these are more than hobbies. They are statements stitched like logos onto the very fabric of our identity. They say: I have time, I have money, I am free. Or at least: I want you to think I am. In the age of performative identity, even solitude can be a social stunt. The silence of glaciers echoes more than the purity of nature. The mountain, once the place to disappear, now offers the perfect backdrop to be seen.

The Mountain as Spectacle

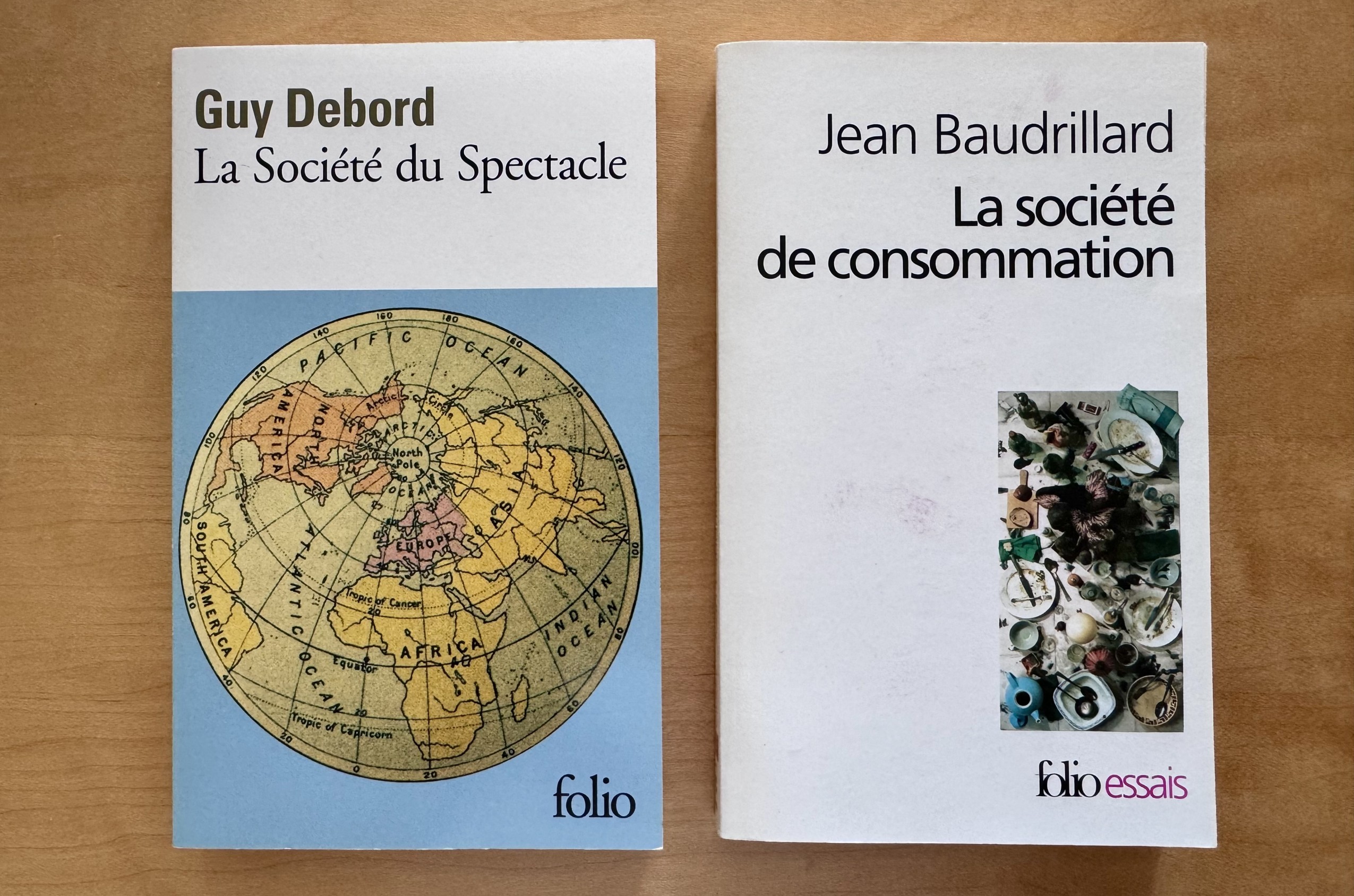

After Guy Debord, “The Society of the Spectacle”, 1967

Debord described a society where life is increasingly experienced indirectly, through its representation. Reality is replaced by its own image, by its embellished and augmented projection. The spectacle, he wrote, is not a collection of images, but a social relationship mediated by them. Life becomes performance. Experience loses its essence and becomes image. And the mountains, of course, become a theater.

Every summit is now a stage. Every ascent, a script. The most solitary pursuits are filmed, edited, and shared. GoPro or drone videos of dizzying ski descents. Wide-angle shots of sickening ridges. Wind-whipped bivouacs streamed live on Instagram. TikTok influencers posing in minidress and city shoes on high-altitude glaciers. The repertoire is broad, like the Netflix menu.

Mountain heroes are no longer just athletes. They are performers. Ueli Steck sprinting up the Heckmair route on the Eiger’s Nordwand in 2 hours and 22 minutes. Climbing the south face of Annapurna I in 28 hours—a route that took the first ascent team in 1950 two full months to conquer. Then, in the summer of 2015, Ueli climbed all 82 Alpine 4000-meter peaks in just 62 days. In 2024, Kilian Jornet came along and repeated the odyssey in only 19 days.

In the Himalayas, Nirmal Purja ticked off all fourteen 8000ers in 6 months in 2019. Four years later, Kristin Harila did it in just 3 months. Reinhold Messner needed 16 years—between 1970 and 1986—to achieve the same feat, doing it the hard way.

Alex Honnold dangling from a two-finger hold halfway up El Capitan, ropeless and alone, topping out in 3 hours and 56 minutes. How long will his record still hold?

It’s no longer about being the first to climb a summit—they’ve all been climbed. The game now is how. The new gods, as well as the new demons, dwell in the details. How fast? With or without oxygen? In alpine style or siege-style with Sherpas? With or without ropes? Summer or winter? In clothes or, like Wim Hof in 2007, in shorts? (Yes, believe it or not, he made it to 7,400 meters on Everest… in shorts.)

By the time one record is set, another is already in the making—faster, flashier, harder. In a blink of an eye, the hero of the day steps into the spotlight with some insane performance. In the age of doomscrolling, where audience's attention span rivals that of a goldfish or titmouse, awe is fleeting. We marvel, then we swipe and forget, snacking stories and content like popcorn. The names of the old pioneers were carved in stone. Today’s are written in sand.

Climbing mountains is no longer a quiet reckoning with the self, but a public act. A performance measured in metrics, views, likes and shares. The sacred gives way to the micro-spectacular. What matters isn’t the experience, but how well it plays. And eventually, how well it pays. The mountain, once an uncorrupted sanctuary, has become a Roman coliseum, lined with red-carpet gondolas and flashlights for five-minute-glory stars.

The Mountain as Commodity

After Jean Baudrillard, “La société de consommation”, 1970

Baudrillard anticipated a big shift: we no longer consume objects for their function, but for what they signify. Meaning overtakes utility. Objects become valuable through their ability to be part of a symbolic system shaped by desires and aspirations. Consumption is no longer about need; it’s about narrative. And through this lens, nothing escapes commodification. Not even nature. Not even mountains.

The mountain has become a product. A service. A branded experience. A business.

But even Baudrillard might not have foreseen how far this would go. In today’s hyper-capitalist system, mountains are packaged into all-inclusive offers, promoted through algorithms and AI-driven ads. The “wild” is padded with Wi-Fi, fancy restaurants and wellness zones. Danger is managed. Adventure is domesticated. Summits are booked. Performance is bought.

High mountains have become jammed routes, stampeded by jumar-wielding puppets clipped to fixed ropes. In 1993, a climbing permit for Everest on the Nepali side cost no more than $500. A year later, it was ten times higher. Within two more years, nearly a hundredfold. Yet, demand didn’t falter. Crowds multiplied, propelled by large media groups and private sponsors. Supply meets demand, a textbook market law, even in the death zone.

Meanwhile, a new breed of mountaineers transforms peaks into lucrative platforms and feats into brands. Kilian Jornet monetizes his endurance through a dedicated trail brand. Nirmal Purja turns his records into marketing leverage for his guiding company. Inoxtag’s Everest climb racked up 44 million YouTube views. How much is that worth? As Bowie once said: “And the papers want to know whose shirt you wear…”

Climbing is no longer about writing history. It’s about generating clicks, shares, and ROI. And why not? It’s a profitable business model. But when mountains become marketing, a piece of their soul may quietly slip away.

On the Verge of the Crevasse

I’m not here to mourn the past or glorify frostbitten heroes from the golden age.

I know things change. And I welcome it.

I’m not against the comforts, the gear, or the videos—I use them too. They are part of our time.

But in this age of hyper-representation and ultra-consumption, a crevasse has opened wide.

Mountains today are both mirror and refuge.

A mirror reflecting our contradictions: our thirst for solitude and our obsession with recognition, our longing for purity and our fixation on profit, our desire to face the wild and our need for comfort.

A refuge, because beyond all the spectacle, the mountain remains what it always was: sharp, cold, wild, sublime. A wall of silence capable of humbling even the noisiest age.

The gods may be gone. The flags, planted. The reels, posted.

But the mountain is still there. And perhaps, beneath the instinct to consume, there still lies something transcendental. A glance toward the summits might still offer us shelter from the bulldozer of modern life.

©Mădălina Diaconescu, July 2025